Incongruities I: Doing Without Having Done, Having Done Without Doing

On the modern separation between the activities of the mind and the body and our spiritual malaise of meaning.

Welcome back to The World of Yesterday on Substack. It has been a while: some more on that and what the New Year means to the newsletter later. Today, I wish to frame the concept of incongruities, which will to be used as a backdrop to the argument that the long-held connectivity between mind and body is being actively splintered by the machinations of modern life. I argue that the activity of the mind and the activity of the body are being separated, which is resulting in the increased sense of both doing without having done (the body acting without the mind), and doing without having done (the mind acting without the body). This separation can be categorized as an incongruity, and further, might account for some part of the modern meaning malaise we are collectively experiencing.

On Incongruities

I’m drawn to incongruities. Let me say that another way: my mind naturally seeks out incongruities, like the way metal detectors look for treasures underneath the sand. I feel hardly alone in this predilection to such an awareness; for it is simply the habit of pattern-seeking and active pattern monitoring is a distinctly human quality. Our particular awareness of patterns seems at least partially related to an instinctual response to changing conditions and what issues those changing conditions could possibly bring about. For instance, a dangerous situation is a potential outcome of an abrupt change. Danger might be when (might being the key term here) it is consistently quiet and then it suddenly becomes loud. The result of the sudden transition from quiet to loud, based on the established pattern of quiet, is what I assert to be one type of incongruity. Incongruities deal in the realm of presumed suitability, and to this end, the literal term does originate from the Latin word congruus (meaning agreeing or suitable), though I wish to go beyond such a strict definition.

Established patterns are expected patterns. If on an airplane, and the airplane starts making lots of noise as it is about to take off, that noise and the changed condition it brings seems quite suitable. However, if you are in a quiet forest at night, a sudden loud noise is not so easily digestible. Incongruities are when patterns change - behavioural patterns, environmental patterns, economic patterns, social patterns, etc - in a way that is not in keeping, that is out of place, with their previously established qualities. On this last point, take a green leaf, a green leaf, and then a red leaf. While that red leaf might be inferred as a changing pattern, its difference is not necessarily an incongruity for the reason that the red nature of the leaf is an expected outcome, a necessary outcome, in fact, to a leaf’s initial green nature. The leaf that is red is just as much as suitable to the leaf’s greater nature as one that is green. A leaf turning blue might be an incongruity, however, because the a leaf turning blue seems to be out of place to a leaf’s nature. Whether the incongruity turns out to be neutral, positive, or negative depends on the suitability of the new condition. The changing of a leaf’s colour to blue might be a neutral in this regard, unless it became poisonous as a result, for instance, and would then be negative.

Incongruities as the Story

It can be said that the world progresses through a series of incongruities, and an important element of incongruities is that they can turn out to be positive or negative. This is not much of a statement: change can be negative just as much as it can be positive. While it will be a negative incongruity, the changing relationship between mind and body, that we will come to focus on, incongruities just as likely can contain positive elements.

Take the positive, founding role incongruities take in the establishment of stories. Writer (and new Substack author) George Saunders, explains in his book on stories, A Swim In the Pond in the Rain, that stories are borne, that stories exist in the first place, out of the author marking a difference from the established status quo’s of the presented world. In other words, stories exist out of an author creating an incongruity. Otherwise, a story fails to draw interest - it remains a consistent record of unchanged fact, and perhaps ceases to even be a story.

The following story by Jonas Ressem (on his relatively new Substack) encapsulates this effect:

In The Balcony, the man opens the white door to the balcony: something that is the usual. He opens the white door to the balcony: something that is the usual, again. He opens the white door to the balcony: something that is different; or, a story. Stories exist not only in the difference but because of the difference. Stories exist because of incongruities. Whether the story is a dream or a nightmare is up to what that incongruity turns out to be.

Incongruities of potential negative significance are worth exploring even if they ultimately either don’t amount to anything or don’t end up warranting further concern. I made a note earlier on the fact that a noise potentially being the cause of danger is more important than whether or not there is actually danger. A lot of times a sudden loudness turns out to be nothing or nothing important. By extension, there is a lot under the sand that our metal detector is now aware of that is not metal, but there is metal we have found as well. A metal detector will detect lots of things that are not metal, but at the same time it should detect everything that is metal. With incongruities, it is better to view seemingly unsuitable changes as potential sources of concern and to therefore prefer false positives than missed positives. The one case a predator lurks in the bushes is worth looking 1000 times for it and finding nothing.

Enough About Incongruities Already

As established, while incongruities can simply be signal of progress or change, they can also be a representation of disorder. Indeed, incongruities can have many possible qualities. Of negative incongruities, the downside might be so minimal that the changed pattern is inconsequential and can hardly be considered negative at all. So what sort of incongruity has the metal detector of my mind attempted to uncover here? I take the incongruity this essay focuses on, the altering relationship between mind and body, to be more on the nightmarish side, to be in the potential danger category. As stated, these particular types of incongruities, those that are negative and potentially significant, harbour the most detrimental outcomes. The separation of mind and body could be nothing, but it might be something, and might be something irreversibly harmful at that.

Different versions of this essay have made the concept of incongruities so needlessly complicated that in struggling to achieve coherence I found myself building a foundation that was not only too expansive for the small house it is meant to support but also too weak to suit its purpose. Out of fear of over-complication, please excuse the directness of the following: the observation I am making boils down to the fact that established patterns change, whether naturally or unnaturally, that an unnatural change of pattern is called an incongruity, and that sometimes (but not always), the resulting condition the change of pattern produces works out in a way that has negative effect that can sometimes be significant (but not always). I am only flagging a changing pattern I believe has negative consequences.

Incongruities can be both cause and the effect of change; yes, incongruities are the change, but a specific type that is out of place (whether the change turns out to be suitable or unsuitable) in comparison to prior conditions. Simply, some patterns changing result in a causal relationship to other patterns changing. In this way, incongruities not only build on top of one another, but one incongruity can be the cause, another incongruity might be the effect of this cause, and also concurrently the cause of another incongruity, and so on. In other words, incongruities can build up on top of each other. A changing of patterns often results in a snowball effect of further changing patterns. The world is not stable, nor would we want it to be, but when the world changes in a way that is negative, that is unsuitable to itself by being at odds with its own nature (as in the case of the separation of mind and body), the effects are worth exploring, so that ideally they might be reversed.

Take change in the weather for instance. A change within the bounds of previously established weather conditions, no matter how much of a change, is not a necessarily an incongruity. The change falls within its own nature, like the green leaf turning red. Now, take the appearance of acid rain, a phenomenon which doesn’t seem to be a naturally developing quality of precipitation cycles. Acid rain, on top of rain that is, well, not ‘acidic’ is a significant, negative, incongruity. But what causes it? Well, acid rain turned out to be largely caused by increased sulfur dioxide emissions (an incongruity), which in turn was mostly credited to more coal-fired power plants (another incongruity). Acid rain, as an incongruity (rain, rain, acid rain) was the effect of an underlying incongruity (no coal emissions, no coal emissions, coal emissions), but also the cause of further incongruities (such as destroyed environments). We live in a patterned, causal world. Everything is progress until it is regression.

So we have, to finish the framework, from a human perspective:

Natural change (Congruities, in keeping/place with previously established nature)

Example: An apple becoming rotten.

Example: A green leaf turning red.

Unnatural change (Incongruities, out of keeping/place with previously established nature)

Positive incongruities (suitable to previously established nature).

Example: An apple evolving to have more nutrients.

Example: A leaf becoming more beautiful.

Negative incongruities (unsuitable to previously established nature).

Consequential negative incongruities (changes have a meaningful effect).

Example: The separation between the activity of the mind and activity of the body.

Example: An apple evolving to become poisonous.

Example: A leaf that grows sharp edges.

Inconsequential negative incongruities (changes, even if negative, lack a meaningful effect.

Example: An apple losing some shelf-life.

Example: A leaf turning blue.

There is some additional technical lingo on incongruities added as a postscript.

The Fading Alignment of Mind and Body

The particular changing pattern I’m most interested in here is the separation between the activity of the mind and the activity of the body in modern life. Basically, I believe that for a long time mind and body were generally doing the same things and now they are not, or least they are not to a greater degree than has been experienced before. Along the lines of incongruities having a causal relationships to other incongruities — being the causes of each other’s effects — I wonder if this separation might be a a possible cause of a potentially related incongruity: the meaning crisis as described by John Vervaeke that our society is experiencing. Any explanation to such a complex phenomena is bound to have a multivariate cause, but perhaps this incongruity is one variable, maybe a significant variable, as in the effect of sulfur emissions from coal-burning to the presence of acid rain.

Nevertheless, here is what I observe: our minds and bodies were always more connected that they are now. It seems like more and more it is only either our minds or our bodies working, or at least recognizing that they are themselves working. I think a simple way to refer to the established relationship between the body and mind was one of support and reinforcement. Now, our minds and bodies live and wander the world mostly alone. At a small-scale, some separation has always occurred. Exercise seems a domain of the body. Likewise, dreaming seems to be practice of the mind. The previously established separation was akin to your parents allowing you to go play in the neighbourhood. Now, with our increased separation, we have gone beyond our instruction, left our neighbourhood and ventured deep into the forest. I don’t know if we know our way back.

Or maybe it is exactly the reverse, for it is not so much that our bodies and minds are wondering the world alone, but more so that they are not going anywhere at all. At an increasing percentage, people rarely leave their homes at all, and some of the biggest adventures we go on are completed inside the borders of a screen. With enough money is it possible to subsist completely through a series of consolidating applications, whether it be grocery delivery, Amazon, Peloton. The allure of doing something without doing anything, without going anywhere, has never been greater. Has it ever been as possible to live without actually doing anything?

Then, there is the matter of misinterpretation between our minds and bodies which may be a further spark to the feeling of spiritual malaise. The argued separation between mind and body is paradoxical, for our minds and bodies remain in exactly the same place in relation to each other as they always have been. Neither our bodies and minds can just be turned off and they watch what the other is doing, though likely without comprehension of what the other is doing. Our minds and bodies are not only doing different things, but barely interpreting the activity of the other at all. We do without having done, we have done without doing. I think these senses are relatively new, at such scale, based on the unfulfilling nature of our modern activities.

I discussed some few weeks ago how we use the time we are given, but even through some modern forms of work allowed by technological time, what do we achieve physically? An email, a sound line of code, an API connection, a database made more efficient: do our bodies understand these creations? Even in writing this essay on my computer, I feel as if I have merely tapped on worn plastic keys rather than having actually written something. If my hands and fingers were exhausted from writing by hand, perhaps my body could understand what it was being used for. I’m not sure it has. And thus I am overcome by the feeling of restlessness: despite my hard work I feel as though I haven’t worked at all.

There is a popular refrain: ‘It’s Time to Build.’ Indeed it is, but surely some forms of building are more desirable and beneficial than others. With many things we are building such as apps and websites, our bodies feel as though they haven’t built anything, hardly recognizing that anything has even been done, and in its misunderstanding deny our selves a feeling of full satisfaction. In an increasingly remote work environment brought on by the pandemic our bodies can hardly recognize that our minds have both gone to, and subsequently left, work. Or even that they have arrived at all.

Perhaps the point of all this is that our bodies are not fooled. They revolt against their condition, and the object of their revolt is us. We do so much, and yet we still feel, on some level, as if we haven’t done anything at all. Is this not a significant source of our meaning crisis?

We do not suffer alone. Collectively, our physical world deteriorates as the virtual world thrives. This fact is best exemplified through the rise of the Metaverse/Metacurse/Zuckerverse/Zuckercurse, a domain I will explore further in Part II of the essay. As it will turn out, I am generally in favour of the virtual world, but not if it is at expense of the one that is real, the one in which we actually reside.

For, we are buried in the ground and not the server.

The World of Yesterday in 2022

It has been a good couple months for writing, though this would not be evident from following my Substack. Posting the first newsletter in September was enough to convince me that my idea of wanting to be a writer was absolutely true. I’ve been exploring for the past few months what kind of writer I mean to be. As for Substack, it allowed for a necessary lesson of writing in public: a lot of people read my first post, less second, less third still, less again fourth. It’s not unexpected, but it is a like crossing a river you knew was there anyway. I’ve realized that habit is more important to quality, that a consistent habit drives quality by the onus you have to put your nose down and find it. From here on out in 2022, I will post something every week (likely on Friday’s, occasionally Monday’s). I need not make them all so grand, and they might start being good. Anything is more than a blank page.

Here is what I say to myself: keep going.

Here is what I ask of you, humbly: keep reading.

I will be posting a schedule next week of planned posts to help hold myself accountable, and help you know what to expect from me and The World of Yesterday. Thanks for reading, and speak soon.

All the best,

Charlie

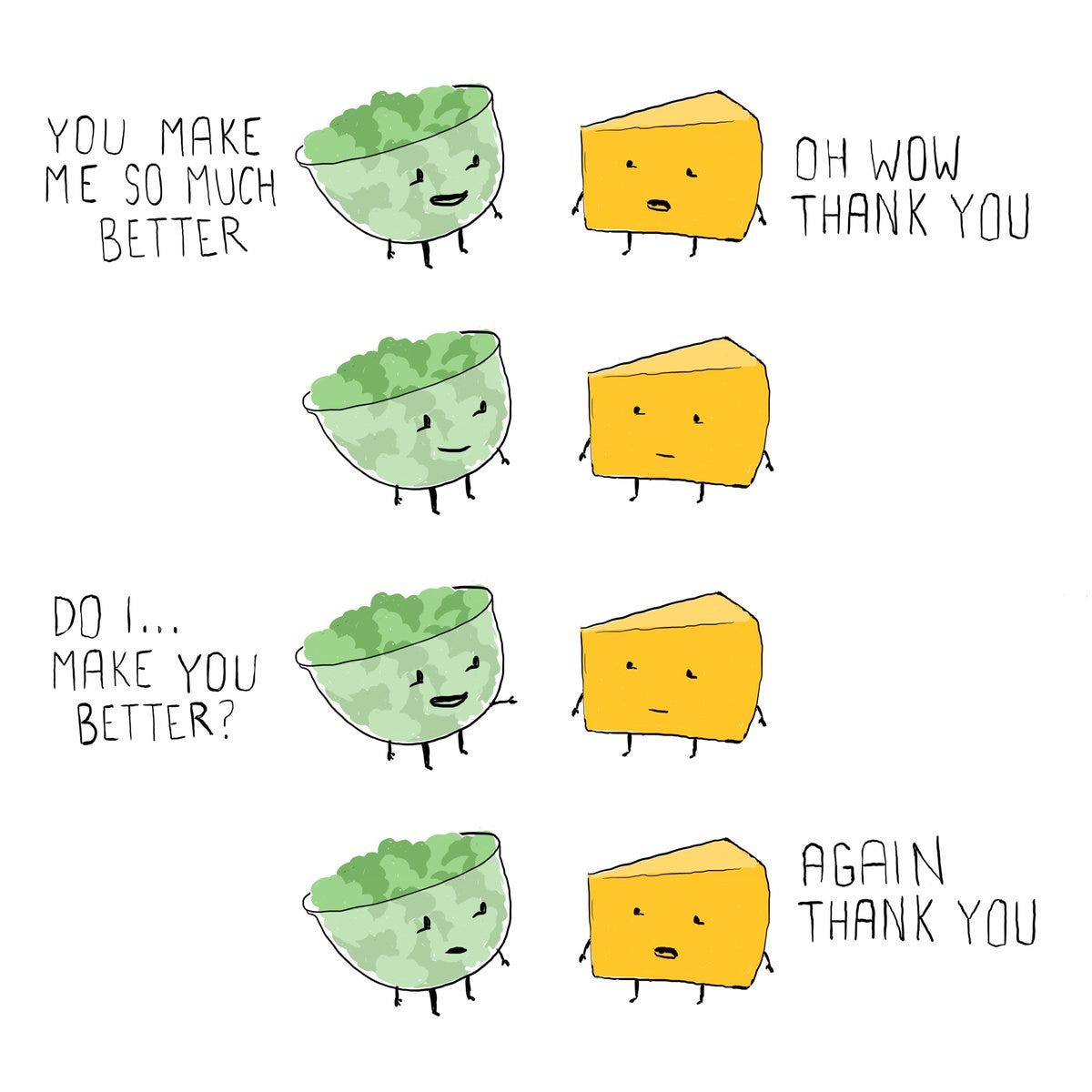

Further Technicalities

An incongruity is borne out of the baseline quality of x being in accordance with y, where both x and y are interchangeable, so that x and y might be in accordance with each other (not an incongruity), but x and z are not (an incongruity), and v and y are not (an incongruity), but w and y are (not an incongruity), and so on, based on the resulting suitability. For example, say apples are x and cheese is y. Now, if y is suddenly substituted with z, which is fish, there is an incongruity based on the incompatibility of cheese and fish. Instead, if apples (x) are substituted with crackers (w), you have cheese and crackers (y and w), which is just as much as an incongruity (being an incompatibility to the existing order of apples and cheese), but this time it works because cheese and crackers are suitable.