Part 1 — Consider the Moralist (I)

Part 2 — Consider the Moralist (II)

VI

But is the pursuit selfish? Do we say the pursuit is for others, for the collective, when it is really for ourselves. That we feel ourselves the greater for not becoming ‘involved’, watching life pass us by, but watching, not necessarily passive, because we think we are too good for it, but in reality we are really too weak and cowardly for it?

Julian Barnes, Flaubert’s Parrot

The ones who go posing as moralists are the worst. Cost-free morals. Full of great ways for others to improve without any expense to themselves. There’s an ego thing in there, too. They use the morals to make someone else look inferior and that way look better themselves. It doesn’t matter what the moral code is - religious morals, political morals, racist morals, capitalist morals, feminist morals, hippie morals - they’re all the same. The moral codes change but the meanness and the egotism stay the same.

Robert Pirsig, Lila

The merit of Kästner’s moralism is what is being considered above all else through Going to the Dogs. The major question of the book—the proposition it dabbles in and around (and literally jumps into)—is whether there is honour in the stance of objective observation; whether a “policy of inaction” or a proclivity for sitting on the fence are courageous choices, in all, if being a moralist is desirable, laudable, and virtuous. Fabian’s life, itself a literary extension of Kästner, is a continued struggle on this general problem of moralism.

Although Kästner’s moralism is marked by a lack of participation, it cannot be defined by a complete absence of it. It can be said that to be a moralist is to participate without participating fully. He exists somewhere else, in some moral -limbo, concurrently somewhere outside of the basic reality in which he is nevertheless inextricably integrated. The moralist engages mostly in observatory, third-party activity from the other side of the proverbial shop window. The moralist, then, functions half in the real-world and half in the constant, pressing, judgments of his own mind; he is always consuming, always processing, always rationalizing; always moralizing, never strictly taking part, always thinking of the next move but never making one. If the moralist was a chess-player he would run out of time before he made a mistake. But would this loss of time be a mistake in itself—is the error of omission equivalent to an error of commission?

But it is not complete omission and I do not mean to indicate that the moralist completely refrains from any critique or doesn’t hope to impart any measure of influence. It was said that the moralist, like a compass, points in a direction but does not necessarily move in that direction. In another sense, the moralist might explore the meaning of life but wouldn’t pronounce his findings, believing that it is incumbent for others to accede to any meaning by their own minds. We recall that Kästner “wanted people to listen and reflect before it was too late.”

And accordingly, Kästner did supply material for listening and reflection. His writing was of such a persuasion that the Gestapo summoned him for interrogations in both 1934 and 1937. But such political independence only aroused more criticism from a wider net of sources, who either did not realize or not appreciate that Kästner’s fundamental capability to document the Nazi horrors was owing to his relative neutrality. For, one cannot observe with a bullet in one’s skull. Indeed, the proposition is to be perched on a fence ten feet above the ground and not six feet under it. If Kästner speaks out too soon, offends, acts, gets caught, he loses the ability to watch, observe, report, condemn. Kästner’s unique handling of a such a predicament is never more evident than his attendance at the burning of his own books; Kästner was the only person to be standing around the pyre of books whose name was carved into some of their spines. Remarkably, Kästner was safe enough to be there, though endangered enough to recognize the shape of the letters that formed his own titles through the flames. And perhaps it is only the moralist who can understand the possibility of watching your own books burn without either running into the fire to save them or being chased after. Kästner stays on his observatory fence, at least for now.

So while Kästner’s moralist is chiefly an observer, it is more precisely that he condemned to observation through the upholding of his adopted role. Sitting on the fence is a choice and the fence itself a strategic position. As has been discussed, it was the non-alignment of this very approach that attracted so much criticism, for all those on any side of the fence could not count Kästner amongst their own. Questions concerning Kästner’s determination to upholding his method continued to be levied at him after the war. If Kästner could see what was happening, why didn’t he do anything or at least say something in more explicit terms? Well, because he was a moralist; the role justified itself.

But this does not necessarily justify the role, a fact by which Kästner is all too aware. As such, in Going to the Dogs, Kästner employs Jacob Fabian to evaluate the competing virtues of action and inaction in addition to chronicling the challenges of being a moralist in the first place. Livingstone observes of Fabian that “[he] is sceptical about the scope for action. He regards himself as a free-floating intellectual. Basing himself on the idea that the entire continent is just living provisionally and that people are ‘swine’, he feels that he can do nothing but observe.” Fabian’s ambivalence about the course of action is paired with a pervading doubt as to whether any action would be worthwhile. “Let us assume for the moment that I really have some function,” he says, “Where is the system in which I can exercise it?”

Fabian is skeptical of the rationality of others and senses a pervasive illogic that is embedded into society as a whole. There is little that can be done, for Fabian believes that the ability to think rationally is a trait possessed by only a limited number of individuals who already happen to be rational to begin with: “Rational thinking could be imparted only to a limited number of people and they were rational already.” And the field of rational thought is much smaller than many might realize. As such, it is not only that Fabian feels himself resigned to preaching to the choir, but that the choir he might preach to is sparse, deaf, and not even composed of all those you might expect would be a part of it. For instance, there is an anecdote of an engineer, despite being a profession that one might assume to be implicitly rational, that has suggested creating more land in Europe by the ‘simple’ manoeuvre of lowering the level of the Mediterranean by 700 feet.

At the start of the novel there is a passionate discussion amongst Fabian’s circle of friends about the troubled state of man. Society is not just likened to be a body afflicted with a particular condition, but afflicted past the point of saving by regular means; that is, traditional methods such as political change or economic programs will not help it. Fabian’s friend Malmy, himself an economist, denounces the influence of his own profession, maintaining that “all attempts to overcome the present crisis economically, without a previous change of heart, are just quackery,” in ascribing society’s failure to a ‘spiritual slothfulness.’ “We want things to change, but we do not want to change ourselves,” Malmy laments. “The circulation of blood is poisoned.” Society is in need of a transfusion and not medicine, of a miracle healer rather than a doctor.

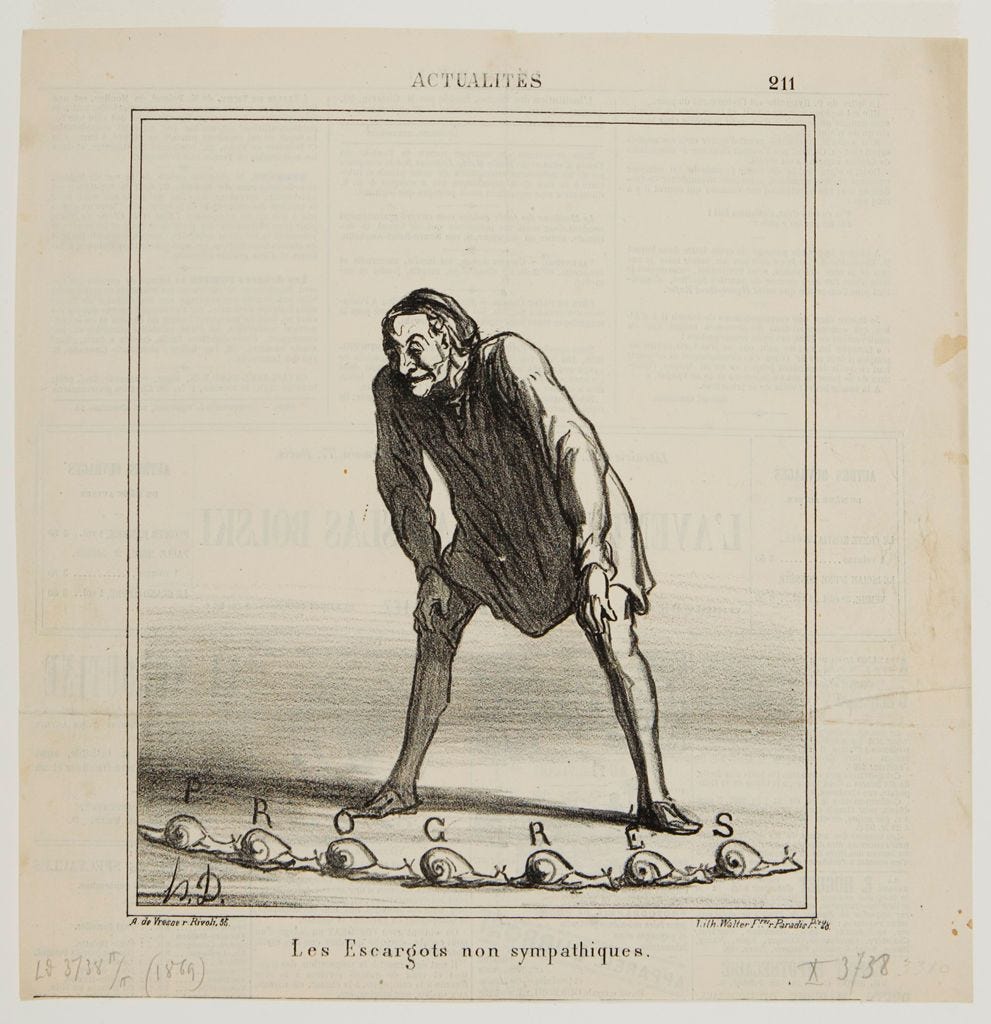

That an economist can believe in no economic path to improvement underscores the collective sense of futility. In another portrayal, the group discusses the below caricature of Daumier, The Unpleasant Snails, which illustrates their contention that man is damned to advancing in circles while nevertheless calling the false advancement progress; “Daumier had drawn a number of snails crawling after each other; that was the pace of human development. But the snails were crawling in a circle.”

This mantle of futility which is taken up most chiefly and consistently by Fabian who must balance his natural impetus for action (for who doesn’t want the world around them to improve) with the ineffectiveness of any measure that he might undertake, all the while having to privately contend with inevitable dismantling of society. Furthermore, whether it is a function of his close observation or because of some sense of general empathy or specific commiseration, Fabian’s inner being reflects the sociopolitical situation that surrounds him. In other words, Fabian is imposed as an inescapable result of his times. Take the instance of his friend demonstrating a concern for Fabian’s mental health; “My dear Stephan…the way you look after me is really touching. But I am not more unhappy than our times. Do you want to make me happier than they? You won’t succeed.” Fabian is like a screen absorbing the projections that it is designed to register.

So what is the moralist to do? What can he do? What responsibility stems for all the knowledge and impressions to which he is privy? Kästner maintains that man is a creature of habit. But of what sort of habit is he? No matter if the moralist is one of the snails or the onlooker, to return to Daumier’s image, the snails proceed—progress, regress—in a circle all the same. Is there anything to be done? Is this granting a seat on the golden fence of moralism a lofty privilege or some sort of curse? Is the moralist honourable for meaning to observe, dishonourable for nevertheless avoiding action, or simply powerless and fated to be tormented from the illusion of opportunity while his being is taunted by the mirage of consequence? Finally, were the horrors Kästner meant to document completely outside of his control and influence? Could he somehow have stopped or impeded or changed the course of the train so destined to depart?

I was sitting in a great waiting-room and its name was Europe. The train was due to leave in a week. I knew that. But no one could tell me where it was going or what would become of me. And now we are again seated in the waiting-room, and again its name is Europe! And again we do not know what will happen. We live provisionally, the crisis goes on without end!

Erich Kästner, Going to the Dogs

And if not, should he have tried?

VII

I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking. Recording the man shaving at the window opposite and the woman in the kimono washing her hair. Some day, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed.

Christopher Isherwood, Goodbye to Berlin

Can you justify yourself with words? And if you cannot justify yourself with words, which is the most rational thing to do, what then?

Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism and Humanism

The background for such a give and take is the chaos of Berlin in the troubling convergence of the dark shadows of the First World War and the fiery silhouettes of the Second. The book begins by Fabian scanning through newspaper headlines that range from the tragic to the absurd, from the economic to the futurist, and back again: “English Airship Disaster near Beauvais, Strychnine Stored with Lentils, Girl of Nine Jumps from Window, Election of Premier — Another Fiasco, Murder in Lainz Zoo, Scandal of Municipal Purchasing Board, Artificial Voice in Waistcoat Pocket, Ruhr Coal-Sales Falling, National Railways — Presentation to Director Neumann, Elephants on Pavement, Coffee Markets Uncertain, Clara Bow Scandal, Expected Strike of 140 000 Metal Workers, Chicago Underworld Drama, Timber Dumping — Negotiations in Moscow, Revolt of Starhemberg Troops.”

This ‘New Objective-style’1 rundown—referring to the genre of literature whose defining quality is its political perspective on reality and often told through a ‘reportage style,’1—provides a wave of setting. But beneath every wave there are seemingly deeper and deeper undercurrents. Most strikingly perhaps is not even the case of a 9-year-old girl committing suicide but the fact that the startling tragedy is taken as “the usual thing'“ and as '“Nothing special.” Something has gone amiss. And still, a newspaper editor adds further uneasy caution, “Believe me, old man, what we make up is not half as bad as what we leave out.”

A biting, suggestive immorality makes its way in the canvas of every situation. There is a woman who sits beside one man in a café while, on account of the man she is with being blind, openly flirting with another across the room. Someone else excitedly expresses the relief about being gifted a large and reasonably priced flat by a man he has recently met: “The furniture was given to me by an old friend, that is to say the friend is old but the friendship is young.” But there is a deceitful catch in the benefactor’s deviancy” “All that belongs to him is a few peep-holes in the doors.” Here is that unmistakable progress of humanity.

Despite his high education, Fabian occupies a menial, temporary, low-paid job as an advertising copywriter (though he maintains his profession as being ‘variable’) which is, by the function of trying to sell goods and services to a consumer base lacking that key element of money, intrinsically futile. There is not a lack or misalignment of demand in society but instead a crisis of resources; people are unable to afford the products being marketed in the first place. Still, Fabian must consider himself fortunate to have the position at all. Berlin had 350,000 unemployed individuals in September 1930. This figure had increased to 650,000 just by late 1932, at which time a quarter of the city's population depended on welfare payments.

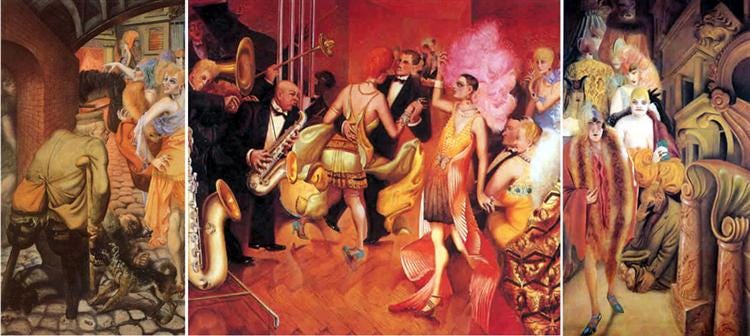

Fabian’s most central role is as the principal propellant to the activities in the novel. It was said that in Going to the Dogs, Kästner offered a deep sketch of his society—this sketch is only possible because Kästner uses Fabian as a stencil to capture the deepest recesses of chaos, perversion, wickedness, and immorality. Fabian is placed in ‘edgy’ circumstances by intention. He frequents brothels, nightclubs, and mess-halls not as places of pleasure nor as milieus in which he intends to participate, but instead as positions from where he might see as much as he can. To Fabian, these debauch settings are artistic, macabre, inspirations, for he is most interested in observing people as they are, rather than how they should be in theory, or imagining how they might be from behind the relative safety and partition of the writing desk.

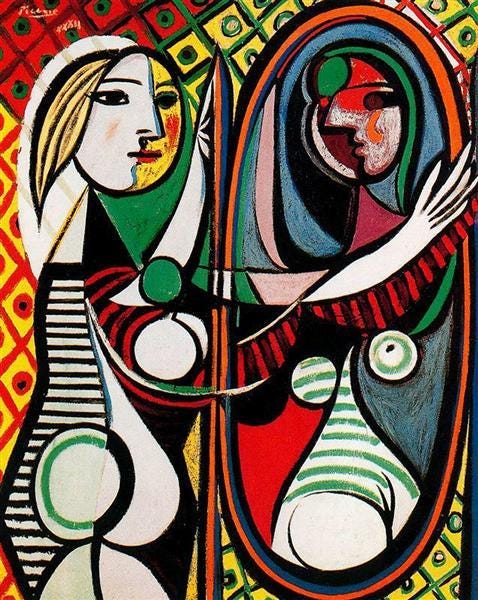

We recall the ‘distorted mirror’ that Kästner holds up to his age and are now in a better position to understand both its composition and the nature of its distortion. Kästner’s mirror is distorted because it does not treat what it reflects evenly. The mirror is a glass pane that is light in some places and darker in others (indeed some of its lightest aspects are its darkest). The mirror is an array of intentional selection and artistic choice; some parts are magnified, some are enhanced, some are enlarged, others are reduced, still others are made invisible entirely. In all, Kästner’s mirror that might be called Going to the Dogs hones in on debauchery at the very extremes of society which he takes to be most representative and revealing of its overall decay.

But Kästner’s distorted mirror is the one Fabian finds himself looking at and reflected by, too. For Fabian is simultaneously viewing the mirror and being seen by the mirror. We are readers 90 years into the future regarding Kästner’s collapsing society with a forlorn curiosity. Fabian is an aspect of the mirror’s active distortion, a passenger on the same sinking ship. In other words, Fabian has the capacity to change his own appearance in the distorted mirror. His reflection is live, his representation is malleable. The paint of his portrait has not dried. As much as Fabian is the propellent, that is, the operator of the mirror that allows its function and aptness of observation, it is his confrontation with this mirror and the wider society the mirror represents— Fabian’s engagement with the problem of moralism—which forms the main storyline of the novel.

The stencil that is Fabian is irretrievably marked by Kästner’s condemnatory brush. We recall that Fabian feels both an interrelatedness to his surroundings, (“But I am not more unhappy than our times”) and a separation from them (seeing himself as a distinct party from ‘Society Ltd.’). In a similar vein, Fabian holds that he is able to be a force of external influence whilst nevertheless being an internal part of that which is being influenced. As such, Fabian is suitably described through his pursuits as a ‘surgeon, dissecting his own soul.’ Indeed, Fabian is both operating and being operated on.

Going to the Dogs is the operating theater of this dual-operation. Composing a series of various activities, encounters, and engagements that strengthen, weaken, advance and detract from the viability, defensibility, and desirability of Fabian’s adopted moralism, the novel considers the consequences of what Fabian does and the ramifications of what he doesn’t. These considerations seem to stem from two central matters of dispute that most directly inform Fabian’s personal response to his general society. First, there is the crucial matter of if society can be saved. Second, there is the follow-up question of if it should be.

If society can be saved, if this depravity and destruction is all a mistake, a wrong turn, an unlucky outcome of undeserved poor fortune, can it be? That is, is it possible to adjust the course of an entire populace and stop the runaway train from departing? What makes the task both more difficult and less worthwhile is the fact that Fabian fundamentally disbelieves in the strong-armed brand of change that would be necessitated to attempt such a rescue. Fabian believes in bringing society to water, not forcing it down their throats. But by this method, many do not learn to drink, and instead wait, submissively, to be delivered water by more aggressive forms of authority or to follow a pied piper to yet another pond that is really a mirage. Fabian tries to influence change without influencing; by ideas provided and adopted rather than arms taken and aimed. For the government’s part, its attempts to patch the sinking ship are satirized and branded as a contributing symptom to the same overall disease.

The characterization is that everyone is being instructed but no one is being helped, and if they are being helped they are really being impeded, or at least helped in a manner that is blindly hierarchical. Fabian at one point notices the various proclamations at city hall that read as follows: “Fabian read the printed notices that hung on the walls. It was forbidden to wear arm-bands. It was forbidden to take return tram tickets from their original owners and make further use of them. It was forbidden to start political discussions or to take part in them. It was announced that a most nourishing meal could be obtained at a certain place for thirty pfennigs. It was announced that persons with such and such an initial had henceforth to come on such and such a day. It was announced that the places and times had been changed for those belonging to certain trades. It was announced. It was forbidden. It was forbidden. It was announced.” Fabian finds fault with the style of the notices, in which he takes to be a never ending series of announcements and banishments delivered in a diminishing top-down manner. It is this same structure that the successive governments would assume to deliver their malevolent instructions to its citizens who were used to their format, if not their malevolence.

A further representation of the challenge comes by way of news of a new government program, who ‘are doing all they can’, to assist the unemployed. “Among other things they’ve started free courses in drawing for the unemployed. That’s a real act of benevolence, gentlemen. First you learn to draw apples and beefsteaks and then you satisfy your hunger with what you’ve drawn. Art-training in the place of grub!” In all, even if the most perfect system exists—and it doesn’t seem to—is that system attainable?

Secondly, if the ideal system is reachable, possible through policy and other methods of government intervention, is its achievement sustaining—able to be carried forth, defended, fought for, upheld? And is this most perfect system even fit for human occupancy in the first place? This second contention examines whether the redemption of society is even a worthwhile endeavor in terms of the underlying baseness of human nature rather than specific human action in Weimar Germany. A pessimistic voice out of Fabian’s circle puts forward the notion that humanity and ‘Utopia’ are two entities at forever odds with one another, “And I tell you when you’ve got your Utopia the people there will still be punching each other on the nose.”

Fabian’s own position draws on his previous statement about the limited capacity for reason in humanity and, while involving more nuance, yields a similar conclusion. “My conviction is that there are only two alternatives for humanity in its present state. Either mankind is dissatisfied with its lot, and then we bash each other over the head in order to improve things, or, and this is a purely hypothetical situation, we are content with ourselves and the universe, and then we commit suicide out of sheer boredom. The result is the same. What use is the most perfect system as long as people remain a lot of swine?”

This segregated diffidence toward society composed of the interrelated senses that not only is there nothing to do but that there is also nothing that can be done is for some time the modus operandi of Fabian and his friends. But the outlook is an unsettled position, and not one that Fabian or his contemporaries can find any lasting comfort or purpose within. It is Fabian’s closest friend, Labude, whose needless death will later mark the most significant point of moral departure for Fabian, who is first to advance the conviction that, in spite of the limited or even impossible chance of success or even some positive influence, that something should be attempted anyway. Labude’s sense is that a low tide beaches all ships, and thus that their futility is itself a futile approach that makes their pathetic rather than honourable. It is Labude’s reckoning foreshadows Fabian’s ultimately fatal attempt at societal influence.

“Good God!” cried Labude. “If everyone thinks as you do, we shall never get things stabilized. Don’t I feel the provisional nature of this age? Is this dissatisfaction your personal privilege? But I’m not content to be a spectator, I try to act rationally.”

“The rational will never achieve power,” said Fabian, “and still less the righteous.”

“Indeed?” Labude went up close to his friend and took hold of his coat-collar with both hands. ‘But should they not dare attempt it?” he asked.Erich Kästner, Going to the Dogs

But should they dare not attempt it? Should Fabian, in spite of whether society can be saved, try to save it anyway? Should Fabian, in spite of whether man should be saved, try to save him anyway? In Flaubert’s Parrot, quoted above, Julian Barnes reflects on whether an artist’s seemingly high-minded ethics is really a base scheme of selfishness and cowardice. “That we feel ourselves the greater for not becoming ‘involved’, watching life pass us by, but watching, not necessarily passive, because we think we are too good for it, but in reality we are really too weak and cowardly for it?” And you are an artist, are you not Mr. Fabian?2 On a related note, Fabian perceives, rather lamentably, in a moment of clarity that occurs near the end of the novel that ‘the righteous have much to bear.’ The righteous, the good, the moral are all ways to focus on a part of the whole, to focus on certain qualities and not others, of one’s moral outlook rather than their human existence. What the righteous have to bear is that while they may be righteous, they are among the corrupted and wicked too. That is, no matter if humanity is a lot of swine, Fabian and Kästner cannot escape being other pigs in the sty, and cannot avoid sharing a fate with those that they condemn, for, they are swine too. An enlightened swine is nevertheless a swine. But what might Fabian do with such enlightenment? What does the moralist do?

Part 4 — TK

Beaumont, Matthew, A Concise Companion to Realism

Reference to James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Original: “You are an artist, are you not, Mr Dedalus?”