Consider the Moralist

I

A moralist is not a moralizer. The latter has the answer before he is asked the question, while the former only has questions after she hears the available answers.

Robert Zaretsky

To become the spectator of one’s own life is to escape the suffering of life.

Oscar Wilde

A man takes up his pen at the behest of his society’s immoral lean and writes about the social decay he has been observing. He does so partly out of shock, partly out of caution, partly out of horror, and partly in the belief in the worthiness of the written word; partly by his steadfast faith in the sovereignty of the individual, partly in doubt about what worthwhile ends individuals are capable of accomplishing with such sovereignty, partly by an artistic exercise, and partly as a personal intellectual project; though mostly, in and anxious but well-formed recognition of the limit to what either he or any other individuals who have detected such winds of spiritual havoc and can do to counter its impending force.

In order to most carefully forecast the impending storm of evil that he expects will culminate out of such foul-seeming weather, the man, unable to grasp the entire adverse system, records individual instances of chaotic impulses instead. The man writes of various happenings and incidents that best demonstrate the infringement of malice, corruption, and general inauspicious behaviour into his city and country that is appears as absurd as it does despicable. And by doing so, the man, whose hearing is good enough to pick up the low rumblings of distant thunder, and whose vision is good enough to see the receding glint of lightning out of the corner of his eye—in lacking the power to in any way personally affect the storm’s imminent approach— does as much as he gauges he can do, does as much as he deems he must do: he writes a warning.

But for the warning he has accordingly provide, the man is ostracised, denounced, and condemned. How dare he to have spoken of these things? For, only a coward and a traitor of the highest degree could so egotistically employ the very same words his nurturing country has so generously taught him in dissent of his very own people. And when this rightly anticipated age of evil inevitably begins and the man finds himself seemingly mercifully outside of the borders he has so futilely attempted to defend, he nevertheless takes the train ‘the wrong way,’ that is, back to the burgeoning core of this wickedness, where, upon arriving, he is a lone man teetering through the blobbing mass at the train station—a blobbing and skittish mass made up of bodies with panicked faces invariably facing his own steadfast resolve, invariably heading in the opposite direction; trying to escape, escaping—and moving against them like a speck of dust that inexplicably floats against the direction of the prevailing wind. Eventually, the man watches at first hand the books that he has written burn, and thus his warnings—once pages of paper and ink—become ashes in a heap of ashes, embers in a scorching pile of waste.

In the end, after the age of evil is defeated—an age of evil more evil than any age evil ever had ever been—those looking for places to host their overflowing blame find an evidently unaffected man with an unaccountable record of silence. And, for the warning he never provided, the man is ostracised, denounced, and condemned. How dare he not have spoken of these things? For, only a coward and a traitor of the highest degree could so egotistically fail to employ the very same words his nurturing country has so generously taught him in favour of his very own people. The only thing the man can point at in defence is a scarred siding of burnt concrete that his incinerating words once lay upon, and the only thing the man can do is take up his pen again and write to a more receptive, lenient audience.

II

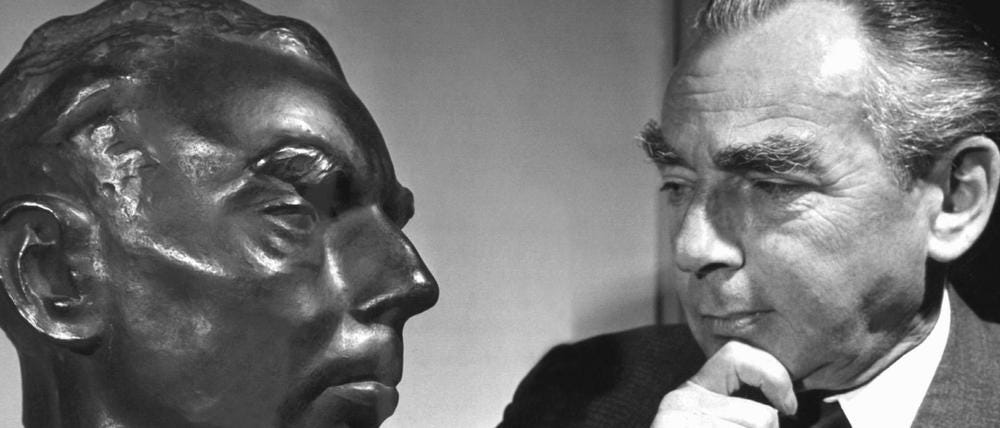

In somewhat loose terms, this narrative anecdote is a vague retelling of some of the most significant events in the artistic life of German author Erich Kästner (1899-1974), which surround the motivation for and ensuing reception to his 1931 satirical novel, Fabian, which offered a cautionary tale about the faltering, stumbling Weimar Republic. Fabian was originally meant to be called Going to the Dogs but was renamed and significantly trimmed Fabian by the publisher in an ineffective manoeuvre to dampen its potential offence.

Today, the book is once again referred to as Going to the Dogs, though it now has the all-important subtitle—The Story of a Moralist—added on. This brilliant novel depicts the shadowy rays cast by the harsh sunset of the Weimar Republic that was to last—its shadows extending ever longer, the sun falling ever lower—until early 1933, whereupon, in the ensuing darkness, as correctly anticipated by Kästner, the gruesome regime that was to take the place of the befallen government filled the bitter vacuum they had been scheming to create.

Going to the Dogs: The Story of a Moralist is a harrowing sketch that arises out of a detailed stencilling of the cavernous surfaces of Berlin. This sketch is drawn by Jacob Fabian, an insider who repeatedly places himself at the very inside in order to allow for such a perspective that is necessary to create such a picture. And yet, Going to the Dogs: The Story of a Moralist is less about Fabian’s specific identity—Fabian’s variability of profession, for example, is immediately and repeatedly underscored whilst his physical attributes are ignored—and even less about the tenebrous final sketch that Fabian actually produces, then it is about, as the novel’s adjusted title quite plainly indicates, the detailed deliberation of the one attribute—the quality of being a moralist—that the novel comes to perform. Accordingly, Going to the Dogs: The Story of a Moralist is about the universal experience of being a moralist rather than Fabian’s particular ordeal in being one; in short, it is the story of the moralist in being a story of a moralist.

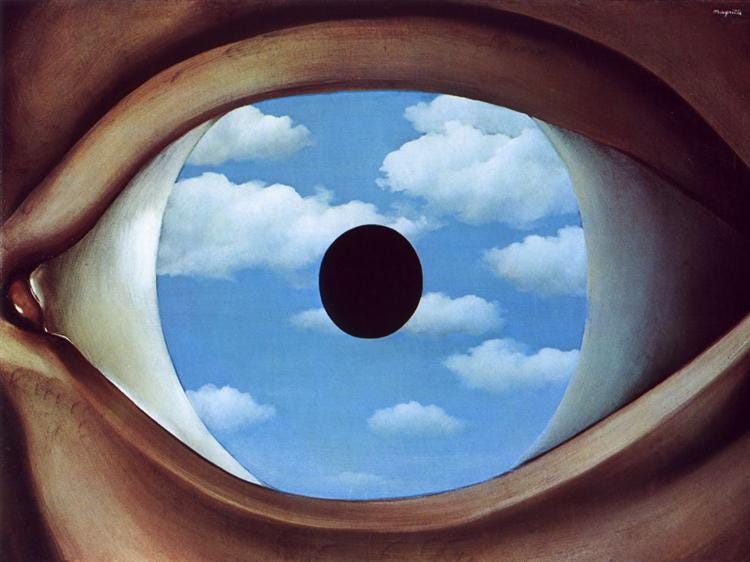

And it is the shared quality of both Kästner and Fabian being moralists—a personality trait that heavily outweighs any other characteristic—to which the novel owes its semi-autobiographical nature. Moralism is the frame of mind in which the sketch itself is drawn from, though it is that precise frame of mind that somehow becomes the focus of the novel more than the particular set of impressions and activities that it produces. In effect, in sketching deepest, darkest Berlin, Kästner—through the efforts of Fabian—sketches himself; and, in sketching himself, sketches all others, in any place, in any time who are likewise afflicted, whether by choice or compulsion, by that same moral temperament. Kästner sketches the moralist. But it remains a partial sketch, one that remains to be finished; one that needs to be coloured in as is seen fit by he who says or thinks or wonders if they are that particular type of person too.

Thus, the story does not concern the particular warnings as much as it is interested in the identity of the individual making them and the treatment of that individual as a result. So while Robert Livingston, who authors the recent NYRB edition’s enlightening introduction, takes the controversies the book has continued to attract to be merely “a sign of its vitality,” I propose that this same controversy is indicative of the sustaining significance of Going to the Dogs and the element of the book most worthy of consideration in the first place. For, the criticism that generates the controversy gives rise from Kästner’s ardent identification as a moralist; in being a man criticised for what he says and doesn’t say, both as soon as it is said (and therefore as soon as it is not said) and for many years thereafter is in a more significant sense the main source of what I have argued to be the novel’s lasting relevance.

Streams of interest flow from such headwaters. Among them: the role and responsibility of art and the artist in society, the struggle of forming and maintaining objective positions, the futility of subjective morality, the power of the individual, the powerless of the individual, the ultimate uncertainty through the adoption of whatever compass one uses to orient the direction of his own life. All such issues of concern inevitably run towards that eventual estuary, all eventually serving the consideration of the moralist as a free-standing figure in society. And Going to the Dogs, like a small boat placed into any of these tributaries, no matter the colour of its hull or size of its sail, seems to end up in this estuary too. 1931 Berlin is only one creek the novel passes through—it is not its ultimate destination.

For, after all, the novel is named Going to the Dogs: The Story of a Moralist, not Going to the Dogs: The Story of 1931 Berlin or The Story of 1939 Berlin though the former is certainly the setting for the former and host of the carrying out of Fabian’s prevailing character, of his moralistic disposition, and the latter is what seems to make all this matter in the first place. On the whole, this is the story I mean to write about: the story of a man who warns but doesn’t act, and is criticised on all sides; both for both his warning and for not acting and, then, when the warnings come to fruition, for (falsely) not having warned and for still for not having acted. In this essay, I will consider the moralist and explicitly tell the story of the moralist that Going to the Dogs only tacitly communicates. So what is that story?

III

One cannot answer for his courage when he has never been in danger.

Francois de La Rochefoucauld

Erich Kästner went back. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Kästner found himself in Switzerland; a convenient refuge whose borders most any member of the German radical intelligentsia would have been delighted to find themselves within at the time. But Kästner went back. And when Kästner got back, specifically when his train arrived back to a flighty and frantic Berlin, he was met at the station by his friends and acquaintances—not there to greet him—but instead trying to escape; trying, in fact, to board the very same train that Kästner had only just alighted from minutes before. Here, moving through the station against the desperate crowds, Kästner is like a single speck of dust somehow floating against the prevailing direction of the wind, a single coat-tail in a legion of lapels.

According to the German novelist Hermann Kesten, Kästner went back because he sought to act as a witness to the horrors that he felt were to come. Livingston specifies that Kastner intended to “write a novel a describing the Nazi dictatorship and he wished to have been present throughout so as to be able to step forward as their accuser later on.” And he would prove to be an indisputable witness to the horror. In fact, Kästner was the only author present on the Opernplatz in Berlin on May 10, 1933 to see his own books burn. As Goebbels himself presided over that wicked ceremony, Kästner himself stood by to watch the hideous flame of words—some of which his own—smoulder into the terrible night—a night lit by the flames but made darker by them also.

But the condemnation of Kästner writings, of which Fabian stood as the most forward and accessible representative, did not stop when all its pages had burned into nothingness. In truth, the criticism had hardly begun there either. Livingston notes the novel was criticised on both sides when it was published; on the right, because “its candid account of contemporary morals was felt to be offensive and immoral, and its satirical attack on Germany’s traditions was thought unpatriotic” and, on the left, by critics such as Walter Benjamin, in an essay entitled Left-wing Melancholy (the name encapsulating the critique), because the writing signified reaction without action, that is “political action devoid of any activity,” and was therefore a representation of the argued negativistic inimical attitude of saying without doing which unproductively “stands to the left not just of this or that position, but of every conceivable course of action”. Eventually, as post-war answer-seekers looked back through the rubbled remains of Germany trying to find all those who didn’t do enough, Kästner’s writings were taken to represent the vain positions of such ‘petty bourgeois liberal intellectuals’ that allowed for such destruction.

After the war, when he was permitted to publish books again, Kästner turned much of his attention towards writing for children, as he had done in the past. Kästner maintained that the young were uniquely morally impressionable and thus exclusively fit to host the necessary regeneration of German society. Such a belief in the malleability of the young, on the one hand, and the equally held belief of the frustrating superficiality in the exercise of writing to adults that were so unimpressionable—so frustratingly and dangerously rigid in their impulsively established ways—is a recurrent theme in Going to the Dogs. For instance, an exchange between Fabian and one of the women he comes across in the novel proceeds as follows: Fabian advises her, “‘You should assume, until the contrary is indisputably proved, that every person you meet, except children and the very old, is a lunatic. Do as I say, and you will soon find how valuable this advice can be.” The woman looks Fabian up and down. “Shall I begin with you,” she asks. “If you please,” Fabian replies.

Another telling example that ties together the sense of social disarray with the sanctified position of the young takes place in one of Fabian’s dreams. Stephan Labude, Fabian’s idealist friend, frustratingly addresses a crowd of amateur thieves stealing from one another, effectively forming a circle of theft. “‘Friends! Fellow Citizens! Decency must triumph!’ ‘Of course!’ Yelled the others in chorus, and went on picking each other’s pockets. ‘Those who side with me put up their hands!’ cried Labude. They all put up one hand, but went on stealing with the other. The little girl on the lowest step was the only one who put up both hands.”

It was perhaps also in consideration of the constant criticism that seemingly followed his writing on a string that made it appealing for Kästner to initially become, then eventually return to being, a children’s author. Was it that children could simply enjoy his stories and not accuse him of being on this side or that side, of saying too much or too little, of the wrong thing or the right thing said too directly, of right-wing heresy or of ‘left-wing melancholy’? Whatever his ultimate motivation, Kästner’s proclivity towards writing children’s books was not only a preference but an immense success. One story in particular, Lisa and Lottie (1959), was adapted theatrically on two occasions in the United States—forming the basis to the well-known films eventually named The Parent Trap (1961, 1998). By the time he died in Munich in 1974, Erich Kästner had been nominated for a Nobel Prize in literature seven times between 1962 and 1971 by six separate individuals. And such is another version of the story of Erich Kästner, such is the story of Erich Kästner, a moralist. And such is one story of the moralist. But it is only that—only one story. There is another. There are others.

this was haunting to read about someone who decided to go against a tide streaming out from disastrous tumult, and then be thrown into a thankless rift between opposing crosscurrents, it's a strange relief to see that afterwards there was work that was translated into new media.