A Coward Confesses

A confession is the central concern of A Posthumous Confession, and if the cost of a true confession is $1, then Emants, by his narrator Termeer, offers, past due, a half-torn ten-dollar bill and a freshly shined coin as payment for one.

And yet we happily accept Emants’s seemingly paltry offer; not as sufficient payment for what he attempts to buy—not his confession as a true confession—for we are nonetheless pleased to settle the outstanding account through the value of what is provided instead: the masterpiece that is A Posthumous Confession. The novel is a first-person, semi-autobiographical, psychological meander through the cowardly depths of Termeer’s mind; a winding narrative journey that means to account for how, as the opening line reads, Termeer’s wife has come to be “dead and buried” and to explain how such a context could possibly render Termeer to be, by his resolved impression, “free again”. In all, as will be revealed, at the end of all our exploring, we are left with nothing that can possibly be taken as a confession—a violation of the apparent chief aim of the work—but all the same provided with a sort of beauty through the study of Termeer’s cowardice that no true confession could achieve alone. Throughout this essay, I will pursue the various factors I take to be the source of this unexpected, extraordinary emergence and explore the peculiar beauty of Marcellus Emants’s A Posthumous Confession (1894); peculiar because on the surface, there is nothing beautiful about the novel—it is a first-person chronicle detailing how William Termeer, narrator and protagonist, has come to kill his wife. Be that as it may, A Posthumous Confession is enchanting, daunting, mystifying, revealing, and most of all, true. As a result of the work we find that the beautiful need not always be ‘the good’; it needs only to be ‘the true.’

The Failed Confession of a Coward

Indeed, A Posthumous Confession is defined by the beauty revealed despite its failure to fulfill itself as a confession. There are two ways in particular that A Posthumous Confession fails to materialize into the confession it overtly intends to achieve. I have analogized this shortcoming to be akin to a half-torn one-dollar bill and a freshly shined coin being offered as payment for an $1 item. To continue the analogy further, each deficient half might be taken to represent one side of Termeer’s double-edged, faulty confession; and Termeer’s confession can be more accurately taken as admission to the quality of cowardice that presides over him, dominates his life, and constantly renews itself through his every action, and as an instrument of Emants to obtain artistic status.

The Half-Torn One-Dollar Bill

Here is the half-torn one-dollar bill: Termeer’s confession is not even a confession, by the principle of a confession not being eligible to be given posthumously. Confessions imply a significant active participle, in that confessions ought to shape or be able to shape the remainder of one’s life. Therefore, a confession should only be offered in the true spirit of confession while one is alive so that one is able to live in the light of its revelation. A confession is a mark indicating not only that one has acted wrongly, but is also a mark at the ceasing of wrong action. In the case of posthumous confessions, any immoral acts it references are set in immovable stone.

Because of there being no such thing as a posthumous confession, the title must be an oxymoron employed in intentional jest, perhaps in reference to eminent authors such as Tolstoy (A Confession) and St. Augustine (Confessions) who authored famous works similarly revolving around confessions. In contrast to Termeer’s cowardly version, both Tolstoy and St. Augustine lived their confessions, and of course to take ‘a posthumous confession’ at its word means Termeer is dead by the time his confession is released. I take this sort of confession to not only be false, but also cowardly because the traditional confessional process is cheated. Because of this, a posthumous confession should be taken, at most, as a cowardly admittance of guilt. In all, Termeer’s posthumous confession fails by nature to be a confession like the half-torn bill fails to retain legal tender, though it does fail for this reason alone.

The Freshly Shined Coin

And here is the freshly shined coin: Termeer’s confession is not even a confession because guilt is never admitted. Whether or not the confession is able to be authentic based on the preceding argument—whether the bill is half-torn or 6/10th torn—the bill is anyways burned before it is offered. While Termeer is fast and frequent to admit to the act of murdering his wife (he often catches himself shouting of the fact when by himself)—a crime is never referenced. The freshly shined coin distracts us from the shortcomings of both the item and the sum as a whole; for there is never an admission of guilt here in the first place, never a confession. Termeer means to distract us by the shine of what he writes. His attempted confession is a coin unveiled from under the fold of his shirt, and, angling the coin’s cleaned metal facing towards the sun, handed it to us in a distraction of glimmering light. However, the quarter-shaped disc lacks any etching; it is only a round piece of metal.

More than avoiding any kind of admission of a crime are the explicit excuses made for it, suggested in accordance with Termeer’s fatalist philosophy which will later be explored in detail. Termeer’s reasoning for the crime boils down to him being ‘what he is.’ This is not a concession met with sadness—that of all things Termeer should be a murderer—but a simply fact towards which he feels equanimous. The die can roll six, the die can roll a one (with the same chance of outcome), why should the one feel lesser than the six? The idea is part of a longer argument, “But if such a miserable fate has befallen me solely because I am what I am, and if I see no possibility of getting outside myself so that I can be renovated, as a house-owner can renovate a dwelling unfit for habitation….once I was involved, my conduct was as it had to be. For I am simply what I am.”

Emants claims his conduct was as it had to be, that there was no choice otherwise, that he was resigned to the rigid tracks of fate, yet this conclusion is contained in a book thats title indicates his conduct was a moral failing to which he wishes to confess. So while we have already established that the confession fails for being offered too late, it now fails as well for truly not even being offered at all. In this way, the unfaithful title is a cherry-top act of cowardice, a crowning achievement of cowardice—a ‘cowarding’ achievement—which encapsulates the work and declares its intention of consummating a confession without confessing at all.

In this, A Posthumous Confession is not the confession of a criminal, it is a full admission of a coward (who has nevertheless committed a crime). Yet, it morphs into a work of art by this outcome, and while A Posthumous Confession can never be taken as a legitimate confession, it nevertheless closely resembles that which it is meant to serve as, just like how the half-torn bill closely represents the untarnished one, and the shiny metal disc resembles a coin, despite sharing no monetary equivalence. Remarkably, it becomes something greater, as if it were presented not as a ripped note but instead folded into a beautiful swan, perhaps with a shiny coin that reflects light upon it.

A Posthumous Admission

If ‘a posthumous confession’ is merely an admission after death, why is the title not something closer to what it truly is, something like A Posthumous Admission? My own view is the fallacious title exists as a mechanism to propel two corresponding motives at play in the work; first, to demonstrate Termeer’s cowardice—the confession is cowardly because Termeer wrongly believes it is authentic, and second, to serve Emants’s desire to be an artist—a quick attempt at membership into the ‘Artists That Confess’ club (of Tolstoy and St. Augustine). A Posthumous Confession harbours the attempt of both author and narrator (and perhaps the latter by the former) to make one thing out of another, or more precisely, a greater thing out of a lesser thing.

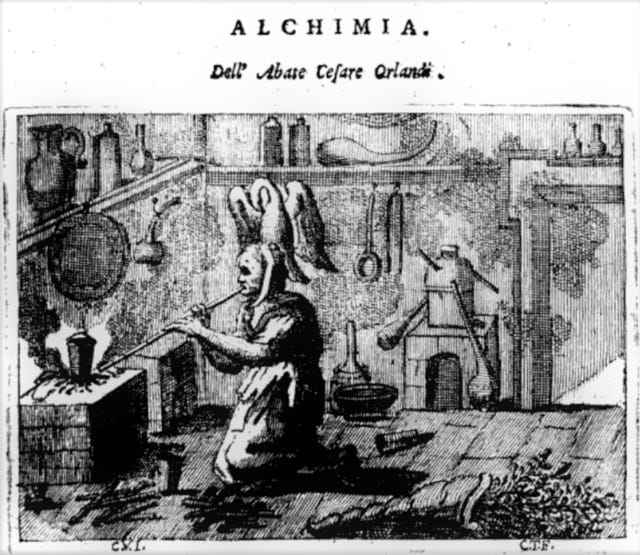

The novel’s translator, Nobel laureate J.M. Coetzee, takes Emants and Termeer to be connected through a literary alchemy: “The author is implicated in his creature’s devious project to transmute the base metal of his self into gold.” On top of Termeer’s futile attempt at a confession is a desperate attempt by Emants to produce a work of art; to rescue a life at the near risk of going into waste by convoking the troubled character and wanting confession of Termeer to act as sacrifice in the pursuit. For, Termeer and his false confession is Emants’s attempt at a work of art, the representation of his artistic spirit, his artistic output, his dart on the board of The Great Conversation. Coetzee again: “In his failure to become a writer - an occupation for which he feels eminently qualified, being ‘sick, highly complex, neurasthenic, in some respects of unsound mind, in other respects perverse’ - we detect what is perhaps Termeer’s deepest crisis.” Crucially, Emants does not throw his dart, which is Termeer, in the usual technique. Emants does not seek gold by the usual method; the novel’s beauty does not derive from traditional means.

Autobiographically, Emants takes the low road in the deviance of Termeer by creating a detestable character rather than an admirable one. Termeer is perhaps the lowest version of his own self, but still, Termeer is good in absolute terms; in his representation he is far from the middle ground, from average, from sullen mediocrity. Termeer is real; why should we mind what road Emants takes in his writing if such genuineness is nevertheless fulfilled? Can one not, as Milton proved, write beautifully of both heaven and hell? Besides, is gold not found in the deep in the recesses of the earth and not the sky?

The previously established deceptive title of A Posthumous Confession is an intentional allusion to such ‘true’ artists like Tolstoy and Augustine; a cheating, desperate attempt of Emants and Termeer to exist on their artistic plane without sharing in their high-minded virtue. And yet the title is also a series of questions. Why must all artists must be virtuous? Why must all truth be found in the good? Termeer doesn’t have one ounce of virtue in him, but in recognition of this diagnosis he thinks all the better for it: "I had often asked myself whether the abnormalities I had seen in myself could not be the sign of an artistic nature.” While Emants has subverted the pristine confessions of Tolstoy and Augustine through his intentionally failed confession, he has ended up the same place as them on the wave of true art; as an artist, as an agent of the highs—and lows—of the human spirit.

The Beauty of the Honesty of a Coward

Yes, I have no money, Emants tells us, no traditional form of value (read, traditional beauty) to give you, but what about this? The offer is not unlike art pieces in Europe that are accepted as ‘donations’ in lieu of taxes. The law would state that a painting is not currency, and yet? And yet, the pictures are accepted. Likewise, we accept what Emants offers too. But what exactly are we taking as sufficient payment? Anything received is delivered through the pure, unfiltered view into the soul of a coward, the admission of a life lived in cowardice. And goodness, it if is not a terrifyingly beautiful sight. Emants finds truth not in moral goodness, but in absolute cowardice, yet it is truth, and beauty, all the same.

So, A Posthumous Confession makes up for its failure to succeed as an authentic confession by becoming something else entirely; the introspective memoir of an anti-hero. To succeed as an introspective work, something need not be necessarily introspectively positive, just contain a high quality of introspectiveness. Such quality is allowed for through by our unrestricted view into Termeer’s soul; by this particular mirror unto nature, to borrow Shakespeare’s image. Somehow, someway, the failure of the confession results in more beauty than if it were to succeed, for in its failure a man overflowing with wretched, poignant, honesty is revealed.

Yes, the beauty and marvel of A Posthumous Confession derives chiefly from its resolute honesty. Here is Termeer, speaking of his marriage, “Of our first two years of marriage,” he begins, “I remember almost nothing. They constitute probably the best period of my life.” The honestly does not reveal a deep moral goodness as we are so accustomed in literature. In this way, the work is reminiscent of Italo Svevo’s Zeno’s Conscience, in which Zeno’s ‘conscience’ is revealed to be far, far from virtuous, but true all the same. I wonder what it says about literature that these works should stand out for being simply honest? Perhaps literature, in an age of misinformation, of dishonesty, of inauthenticity, is not best served by offering it only the best of us, but instead by offering it all of us. Perhaps Emants does this, and his full allowance accounts for much of the work’s beauty.

“How often have I not heard the remark that a person who knows his faults can eliminate them too. How little self-knowledge people must have who speak that way!”

Marcellus Emants, A Posthumous Confession

While some might question the genuineness of Termeer, his habit of deceit seems to be external rather than internal facing. In fact, we are only aware of his external deceitfulness through this internal honesty. Certainly, some disclosures might generate mistrust to some readers; for example, in speaking about his relationship with truth, “I am still loath to give a truthful account when I can cook up a story,” and on recounting his life, “My memory has never been very good,” but to me, the underlying believability of these lines shines through and I might perhaps flag that truth and honesty are something separate. Termeer is unfailingly honest to himself, and chooses to lie only to others. Is this not honesty? How many of us tell the truth to others but lie to ourselves, deceive ourselves, subvert ourselves in the process? Is this not living in falsehood?

Therefore, despite Termeer’s clear affection for lying and stories, I don’t believe that Termeer intends to deceive in his attempt at a confession directly. Termeer hides behind its cowardly contents, sure, though I would posit again that this positioning is external facing mostly the work of Emants. All the facts Termeer provides are true, but their motivations are wrong; Emants would rather make a work of art than allow Termeer to be licensed with a real confession.

More factors combine to reinforce the authenticity of Termeer. Primarily, what does Termeer have to hide in considering the posthumous nature of the confession? Does a criminal, if they want to be a criminal, not yearn to confess to his crime like a wanting liar yearns to confess to his lie? Has the proud liar or the crazed killer even lied or killed if no one else is aware of their indiscretion? Has the criminal or liar even gotten away with something if no one knows anything has been done? Second, it has been written that the moments before death are the only time in life that we are truly honest, and we must assume Termeer writes with the knowledge that his words will not be read until after he is dead.

The Biography of a Coward

Who exactly is Termeer and what more can be said of both him and semi-autobiographical nature of A Posthumous Confession? Termeer and Emants are men younger is disposition than in age. Termeer has never grown up—the death of his father that he never received approval from cemented this one time temporary fact into a permanent reality. What he is given by his father, though, is a substantial inheritance, the majority of which he is never to come into possession of even as an adult due to his cowardice. Termeer’s inability to send a letter to where it needs sending, to apply a signature where something needs signing, to stamp something that needs stamping, et cetera, is a microcosm for his bias toward inaction. That Termeer struggles for guardianship of what is rightfully and lawfully his is proof of his immaturity, and exhibits his behavioural pattern of passiveness which maintains his prolonged youth.

The life of Marcellus Emants (1848–1923) follows a similar pattern, though not nearly to the same extremes. While Emants did not kill any of his three brides, Termeer can be understood as a representation of himself all the same. Born of a well to do family in The Hague (his father was a judge, and seemingly brought his work home—an experience shared by Termeer), Emants began by studying law only (uncourageously) to appease his father, a motive that becomes clearly apparent by the fact that he dropped out of the law faculty immediately after his father’s death in 1871.

In A Posthumous Confession, Termeer’s father dies just as he enters adulthood and thus he secures financial freedom at an early age, and like Emants, perhaps never pursues a career because of this. Still, both Emants and Termeer share the vehement desire to fulfill their existence by making a submission to the inventory of eternity. Perhaps Emants writes of someone, armed with the same historical facts and circumstances, that is the very worst version of himself, who is the embodiment of the lowest outcome of a thousand simulations of moral goodness that his nature allows; the deepest, most evil rung of his subconscious. Termeer is not as much as an alter-ego as a super-ego, one that is within himself, just at the very bottom. Does literature not usually present the other end and are we not grateful for receiving this one?

Forms of Cowardice

“Cowardice has remained the indestructible worm gnawing at the fulfilment of all my wishes.”

Marcellus Emants, A Posthumous Confession

Let us explore further what it means to say that this book is the biography of a coward and for the book to be a bottom feeder of morality. The cowardly confession that attempts to vindicate Termeer of such cowardice committed in the act only further reinforces it. To Termeer, one cowardly act absolves another, and throughout the novel Termeer’s life is conceived as a cascade of cowardice that culminates in a cowardly confession meant to pardon the cowardly act of killing his wife. Termeer seems to live by the mantra: do the most cowardly action at any one moment possible, then another, and another, to cover up whatever field the previous cowardly action has ploughed.

Let us assume a coward to be someone who, wishing to act, does not, and a cowardly action to be, if they do act, an act that is most uncourageous one possible. Termeer knows as much about his habit of cowardice as we do, it is he who gives us the idea in the first place, “But if ever a favourable opportunity presented itself, I hesitated just long enough to let it pass.” Termeer continually refuses to act, whether it be to study, to gain employment, to secure his inheritance, so it is curious he should come to make a decisive decision to kill his wife, the defining action in A Posthumous Confession, the action the confession orbits. Termeer explains that he fears the world: “I was deathly scared of the world,” and more than this feat, he is, “Revolted by all existence.” As a remedy to his disposition, Termeer refuses to take part in the world, choosing instead to protect the sacredness of his l false ideals, “I had beheld my ideal world and felt how impotent I was to enter it.” In refusing to threaten such false ideals he refuses to act, and cowardly fights against the surefire arrival of the future; “As a boy I despaired of ever bringing that future into being. Only a first step was needed, but I was unable to take it.”

The step Termeer eventually takes, the murder of his wife, Anna—the one time in his life he seemingly does what he feels like doing—is even marked deeply by cowardice. The act itself is an act of cowardice and the confession that later accompanies it is, as we have concluded, not even a confession. Termeer kills Anna in her sleep by forcing her to unknowingly swallow great quantities of the sleeping liquid Anna was already partially using. Anna never opens her eyes and dies without the knowledge of being killed; she simply dies - hardly killed by Termeer. By Termeer’s aversion to conflict it is likely that if Anna had the fortune to open her eyes, he would have never gone through with, faced with the barrier of having to act through adversity. Anna never even realizes that she is dying, yet Termeer claims relief from his general cowardice by the act. “After this act I would surely no longer be a coward!”

Termeer’s primary motivation in killing his wife is to no longer be a coward, which only serves to make him more of one. Termeer consumes his livelihood by claiming that after he does something he will no longer be a coward, then goes about doing that thing in the most cowardly way possible, to which his only solution is to commit more cowardly acts, of both commission and omission. The ensuing confession that forms the book is an apology for the consequences of his cowardice, except for the fact that it isn’t an apology at all—it is a justification.

The Philosophy of a Coward

“Is it like that with other people, or does nature grant them the reality of which she concedes to me only the reflection?”

Marcellus Emants, A Posthumous Confession

The Fatalist Coward

The ardent fatalism of Emants and Termeer, and we can drop the distinction between the two versions of the same thing here, accounts for Termeer’s inability to recognize or accept guilt. Coetzee described an essay Emants writes on Turgenev where, ignoring Turgenev, Emants holds that our lives our driven by unconscious forces within us, impelling us to act, and it is only through these actions we can come to understand who we are. Instead of acting in a way in accordance to how we are, according to Emants, we instead are in accordance to the way we act. The action is the primary force of our being, not an output of our control. A Posthumous Confession is not dissimilar to the formation, where in meaning to write a confession, Emants really writes a semi-autobiography with a confessional tone. And the novel is semi-autobiographical because it is not only about Emants; the lens is quickly turned on us: “Respected, honoured, decent, high-minded reader, if you think you have become so excellent by free will, why then are you not even better? Is it because you have not wanted to be, or because you could not?” Isn’t that great?

Under fatalism, our ideals are not in control of our actions, the result of which is an uncomfortable strand of self-knowledge between our ideal selves; how we would like to act, and our real ones; how we are fated to act irregardless of our ideals. Quite often, the distance between the ideal and the true self is vast and is separated by an unbridgeable gap. Coetzee summarizes these two elements as a dual emphasis of the powerlessness of the individual before unconscious inner forces on the one hand, and the disillusionment of coming to maturity on the other. So, not only do we fail to live up to our own expectations, we are always painfully in view of these expectations racing ahead of us, sometimes painfully close, sometimes painfully far.

In the natural development of life do we grow as individuals, or do we grow only more aware of our own shortcomings, whence our ideals can never be realized? In this way, Termeer might argue, why should one meagre individual take responsibility or apologize for the unchangeable machinations of fate? The man that acts with honour has done the same as him; simply acted out what was demanded of him by fate.

“Perhaps someone or other may have said or written of you that you have always shown yourself to be exceptionally good-hearted, a lover of mankind, generous, helpful, and I don’t know what else besides; and then, as the plum on top, he will surely have added, “He could not have acted otherwise even if he wanted to.” “Well, such is the case with me too. But now I ask, why does the phrase that holds praise for you become slanderous when applied to me?”

Marcellus Emants, A Posthumous Confession

There is a game mode of Mario Kart whereby you are able to race against your previous best time on any given track. The record time looks like a ghost-like version of yourself that keeps the best pace, like the way swimmers chase a world record line at the Olympics. If the car in front is the ideal, we are like Mario Kart characters chasing our record time that is not physically possible for us to achieve. A coward might believe that since they can never surpass the ideal, there is no point in trying. I don’t deny the constant battle we wage against our potential, but in my mind, we would be better served to keep chasing anyway and feel fortunate that we have something to chase in the first place. Or, better yet, to look for another route entirely. As William James says, “My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will.”

Crime and Cowardice

The above notion of ‘taking a step’ evokes a central postulation of Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment. Raskolnikov and Termeer are similar up to the point where Raskolnikov talks away his particular sin to the police, in allusion to his great man theory, men of action, who are those that ‘take a step.’ Termeer believes theory absolves morality in action as well, though his philosophy is fatalism rather than indeterminism. Termeer is a similar but even more cowardly version of Raskolnikov, whose cowardice is never overcome by the deep reckoning and spiritual revelation experienced by Raskolnikov.

Let’s look briefly through the general character arc of Raskolnikov throughout Crime and Punishment, as the comparison between him and Termeer is a fascinating character study.

‘H’m…yes…man has the world in his hands, but he’s such a coward that he can’t even grab what’s under his nose…an axiom if ever there was…Here’s a question: what do people fear most? A new step, a new word of their own - that’s what they fear the most. But I’m talking too much. That is why I never do anything. Or maybe it’s because I never do anything that I’m always talking.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment

At this early point in the narrative, Raskolnikov and Termeer are both men defined by inaction. Raskolnikov has authored a series of suggestive papers, but has never acted out any of the theories that his work puts forth.

Crime? What crime?' he cried in a sudden surge of fury. 'I murdered a vile, noxious louse, some hag of a moneylender of no use to anyone, whose murder makes up for forty sins, who sucked the juice from the poor, and that's a crime? I don't even think about it. I don't even think about washing it away. I don't care that you're all prodding me with your "Crime! Crime" Only now do I see the full absurdity of my petty cowardice. Now, when I've already decided to accept this pointless disgrace! I'm despicable and talentless, that's the only reason I've decided, and maybe also because it's in my own interests, as that man suggested...that Porfiry!' 'Brother, brother, what are you saying? You shed blood!' cried Dunya in despair. 'Which everyone sheds,' he rejoined in a kind of frenzy, 'which as always poured like a waterfall, which people pour like champagne, and for which they're crowned in the Capitol and remembered as benefactors of humanity.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment

The both act, both commit a form of grizzly murder, but Termeer murders out of and in cowardice, whereas Raskolnikov murders for an idea, head on. Termeer is even more cowardly because he doesn’t even ascribe his action to any sort of responsibility, only playing out of fate. Raskolnikov may said to be a coward for not admitting to his crime (or acknowledging it as a crime in the first place), allowing another man to be accused, but not in avoiding action. Some could argue that the moneylender killed by Raskolnikov was more deserving of death than Termeer’s wife, though the moneylender’s sister shared in Anna’s innocence.

'If I'm guilty forgive me (although if I'm guilty, I cannot be forgiven).'

Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment

Here is a confession of the sort never offered by Termeer. Raskolnikov does not even wish to be forgiven, which is perhaps the best indication that he might be. Termeer assumes he is forgiven, that any action in the absence of free will is forgivable.

But here a new story begins: the story of a man's gradual renewal and gradual rebirth, of his gradual crossing from one world to another, of his acquaintance with a new, as yet unknown reality.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment

Here is forgiveness; Termeer is of course not given this either.

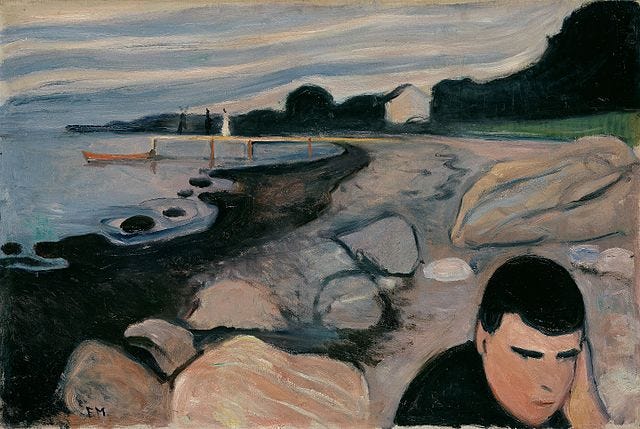

The End of Cowardice

At the end of the novel, we arrive back where we started, in the same room from which Termeer initially departed before his descent down into his soul. Without doubt, to explore Termeer’s soul is to descend, not to ascend. But it is still to find the truth. Indeed, this going down, the act of ‘catabasis’, aligns with the trope of psychoanalysis that truth is to be found in the subconscious, the deeper the better. Emants descends into his soul, like Dante instructs Virgil to descend into the Underworld, and not only finds beauty but also discovers that he is not alone:

“I had become older and therefore more experienced, more adept. The therefore was irrational, but who dares say he is not afflicted with a similar therefore? Beneath the rusty crudities of our old age lie the shining errors of our youth, yet most people seem to labor under the delusion that their life is a development, a progress.”

Marcellus Emants, A Posthumous Confession

In A Posthumous Confession, we are witness to a false, cowardly confession on the triumphs (there are few) and tribulations (many) of a coward. Termeer denies what he is (a coward), fails to accomplish what he means to do (confess), but becomes something anyway, perhaps in his rejection of trying to be anything, or denial of that which he and the work clearly is. Through all that results Termeer’s failure, Emants succeeds in his chief own aim; to produce a work of art. Here is the fundamental dynamic of the work: in not becoming what it aims to be, it transforms into what it is, something higher than the initial aim. In alchemy, it would be like trying to make gold but inadvertently creating diamonds. The alchemist fails; but the purveyor of value succeeds. More beautiful than a confession, I believe, turns out to be the candid admission of not being able to make one. If it is honesty we crave, the truth that we value above all else—and I think we do so rightly—is this book, by virtue of being perfectly forthcoming, not a work of art? Or is merely an honest man, rather than an artist? Emants is aware of the ambiguity, but the ambiguity only serves to make his artistic nature more honest and true.

“No, I was no artist.”

Marcellus Emants, A Posthumous Confession

Has the pure, unadulterated truth ever been so rare? Has the truth always sounded so magical, or was it boring, and mundane, and made us come up with lies and exaggerations in the first place? In being so accustomed to lies and exaggerations, the truth stands out. And I have said the beauty of the novel is devastating, without previously specifying exactly how the devastation originates. It rises out of the following reason: have you ever read something so full, so honest, so true, so full of truth, that it temporarily absolves the urge to write anything yourself—for that reason that anything you might wish to write has already been written, that someone has spoken on your behalf? Have you ever read anything that makes you question what more you have to add? I hope to God that in reading this terrifyingly beautiful book that I have not. And I don’t mean the action Termeer takes as much as his underlying cowardice, for if I am an Emants, may I never find a Termeer in my own depths, or if I do find him, may I never succumb to him.

Termeer, for his part, predicts this fear; “Who knows how many there are who are just like me, yet will only realize it only when they have seen themselves mirrored in me?”

Incredible.